|

Bluebeard’s Castle |

Works That Changed the 20th Century |

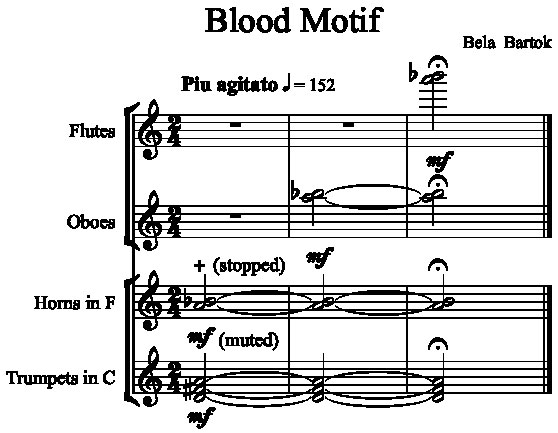

The years 1911-13 were noteworthy years for the development of modern music in the twentieth century. Not only was Béla Bartók creating his expressionist masterpiece, Bluebeard’s Castle, but Igor Stravinsky was working on his primitivist ballet The Rite of Spring, Maurice Ravel was composing his tour de force of impressionism Daphnis and Chloe, and Arnold Schoenberg was writing Pierrot Lunaire as he began to develop an atonal style of music. It was the era of post-romanticism just prior to World War I. Works for huge orchestras were common and three of these works required huge musical resources for performance. Bluebeard’s Castle requires mostly quadruple winds, 4 Flutes with 3 players doubling on Piccolo, 2 Oboes, English Horn, 3 Clarinets with players 1 and 2 doubling on Eb Clarinet and player 3 doubling on Bass Clarinet, 4 Bassoons with player 4 doubling on Contrabasson, 4 Horns, 4 Trumpets, 4 Trombones, and Tuba. The are also 4 offstage trumpets and 4 offstage alto trombones. The remainder of the orchestra consists of 2 Harps, Celeste, Organ, Timpani, Bass Drum, Snare Drum, Tam-Tam, Crash and Suspended Cymbals, Xylophone, Triangle, Wind Machine, and a string section of 16 First Violins, 16 Second Violins, 12 Violas, 8 Cellos, and 8 String Basses. This is quite an accompaniment force for only two singers in the cast, Judith, a soprano, and Bluebeard, a baritone. The libretto to this one act opera was written by Béla Balázs, a Hungarian poet and friend of Bartók and Zoltán Kodály. Due to the onset of World War I and other factors, it didn’t receive its premiere performance until May of 1918 at in Budapest at the Royal Hungarian Opera House. The work was published in the 1920s but received limited performances until after World War II. Part of this is due to the fact the libretto is written in Hungarian, rather than the traditional opera languages of French, Italian, German, or English. The story is based on the tradional French story about a wealthy nobleman whose wives keep disappearing, and specifically on La Barbe bleue by Charles Perrault. In this version of the Bluebeard story, much of the overt horror is replaced with a very expressionist battle of the sexes between Bluebeard and Judith, his latest conquest. She has fallen in love with him, very much against the wishes of her family, and he has brought her to his castle after defeating her family in a war. Now isolated and alone, Judith wants to know all about Bluebeard: what are the things that make him who he is? As they walk through the darkened corridors of his castle, he continually asks her if she is “Frightened?”, giving her the opportunity to leave, but she decides to stay having cutting off all ties with her family. Eventually they come across seven locked doors in the main chamber of the castle. Judith demands that the doors be opened, but Bluebeard refuses, explaining that they are locked private places, not meant for others to see. He tells Judith that she should just love him, and ask no questions about what is behind them. But Judith persists in her demands, keying everything to her love for him, and eventually is able to pry the key for the first door out of his hands. The first door opens up to his torture chamber, and a shocked Judith sees shackles, daggers, racks, pincers, and branding irons accompanied by a multitude of shrieking ascending and descending runs in the woodwinds. The second door reveals his armory of war weapons keyed by military fanfares in the trumpets and horns. The third door is his treasure chamber filled with jewels. Bartók’s clever orchestration for this door is based on a long held D major triad played by muted trumpets, tremolo violas, cellos and harps, flutes in fluttertongue, and continuously repeating arpeggios by the celeste. Two additional countermelodies are played by two solo violins and horns. As Judith observes these rooms, soon she discovers that all the devices are blood encrusted. Key to these scenes and their orchestration is the use of the blood motif, stacks of grating minor second intervals that add to Judith’s horror and appear everytime she notices blood on the implement, weapons, the wall, and the jewels. The example below shows one example: |

|

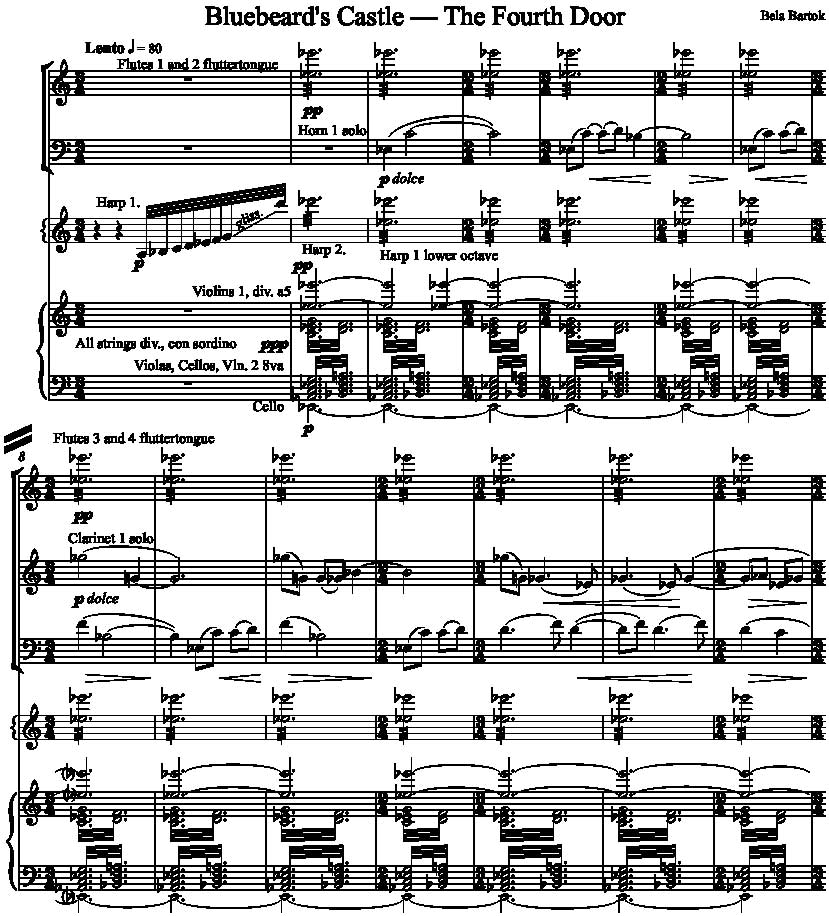

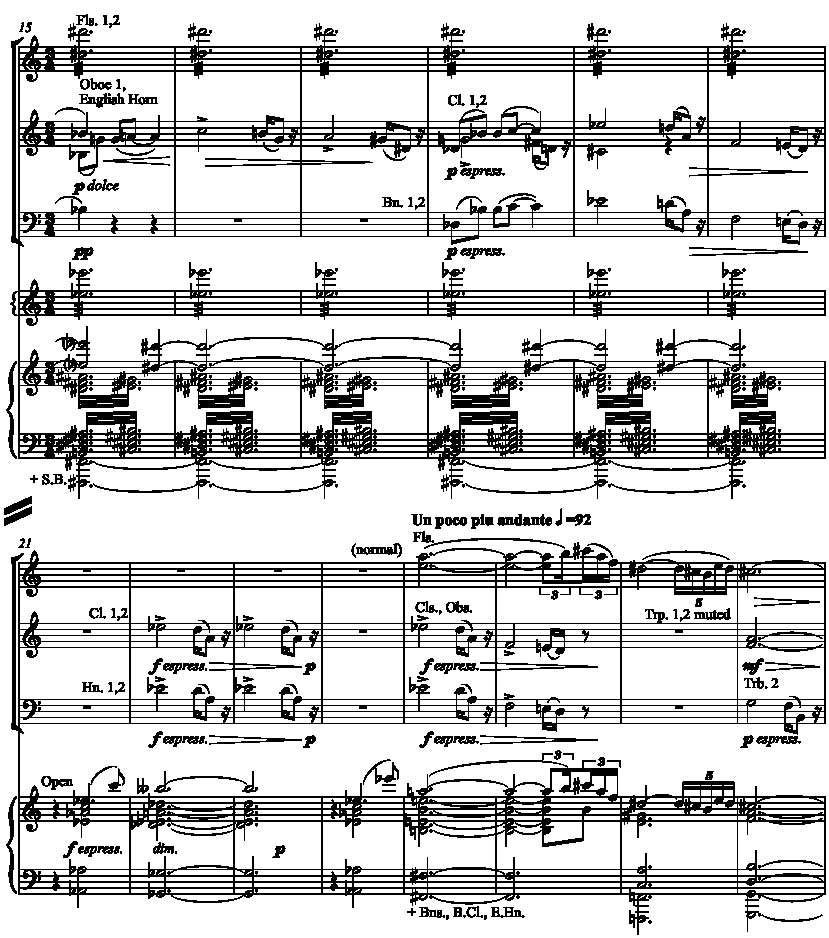

To calm down a more and more agitated Judith, Bluebeard has her open the fourth door, which is his secret garden. This is another creative passage of orchestation, which you can see in detail below. As the door opens, Bartók creates a vibrant sound of nature with high and low pedal point E flats, flute fluttertonguing, harp tremolos, and high and low sustained notes in Violin 1 and low cellos. Inside the pedal points are very soft tremolos on an Ab major seventh chord played by muted second violins, violas, and cellos. There is an extended duet between solo horn and clarinet. Later they are joined by oboe and bassoon. The full string section, now open, plays several passionate phrases, joined by the flute. The flute takes over with an incredible bird-like passage filled with many descending trills and a final run back up to a new pedal point E flat. |

Listen to the excerpt as you follow the score: |

|

|

|

|

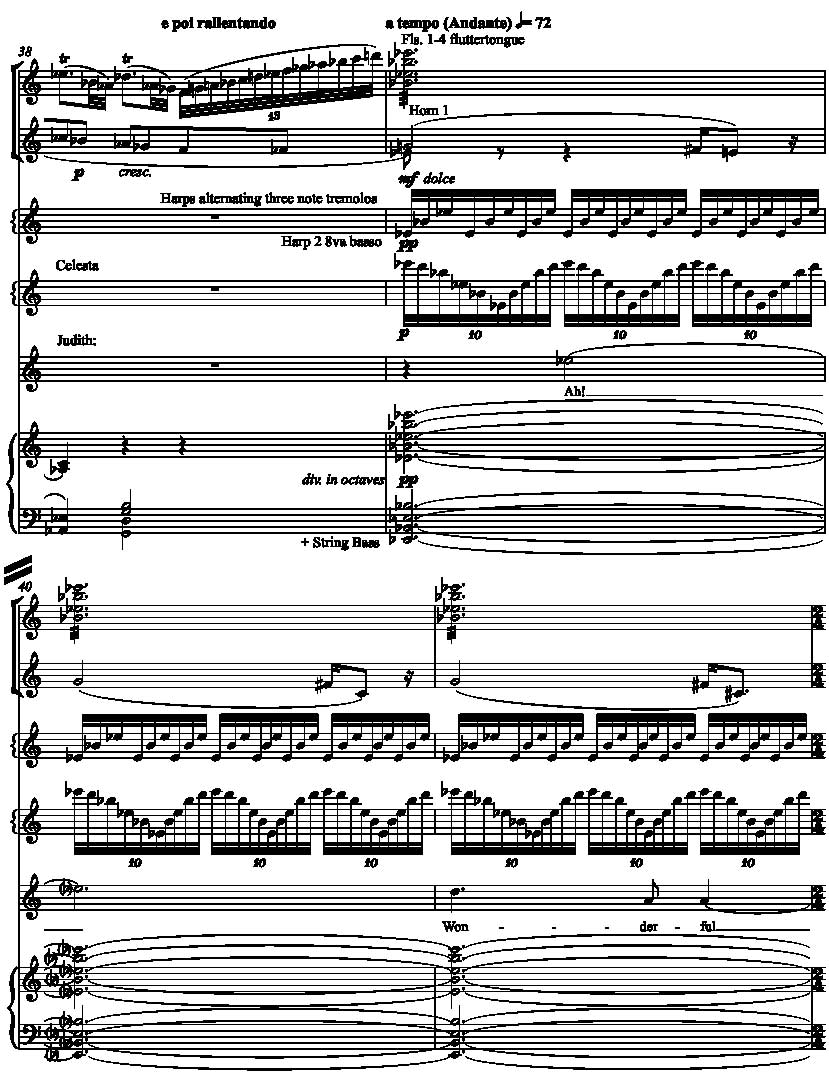

Now all the string section, the harps, fluttertonguing flutes, and celeste play essentially an E flat power chord of Eb and Bb, modulated by figures in the first horn and in Judith’s soprano line singing “Ah, wonderful,” in amazement at the sight before her. Eventually, as with the other doors, Judith discovers blood on the flower petals and we get more reps of the blood motif. In desperation to take her mind off of that, and to impress her with his might and power, Bluebeard orders the fifth door to be opened. You can see this in another blog entry about passages with full organ and full orchestra. There is so much more to be said about Bluebeard’s Castle. The opera delves into the inner emotions and motivations of Bluebeard and Judith, and the dynamic between men and women in their relationships. This was written in the heyday of Sigmund Freud when psychoanalysis of oneself and one’s relationships was taking the scientific world by storm. The castle represents Bluebeard’s past and secret motivations, especially as the final two doors are opened. One apt observation about the roles of Judith and Bluebeard in the opera is that they resemble two hairpins. Bluebeard’s role gradually increases throughout until the end, when he is the only one singing, while Judith’s role is a decrescendo, starting out forceful, demanding and dominating the singing as she strives to know more and more about Bluebeard, and her shock and withdrawal inter herself as she discovers the truth about him. This opera is also noteworthy because it has specific colors associated with each door, especially significant in a story line with not much action. There are performances scheduled for early October, 2020 by the San Francisco Symphony. As this is somewhat infrequently performed, if you are interested in this piece and the work of Bartók, you should definitely attend. |